How folk remedies can fuel misinformation

VIEWPOINT: They may sound benign, but they can cause a threat to public health

By Katrine K. Donois, Anglia Ruskin University, and Hassan Vally, Deakin University

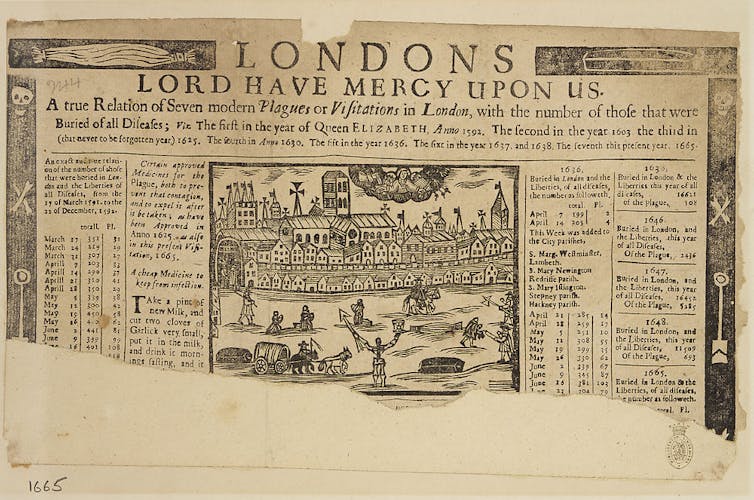

When London faced the bubonic plague in 1665, many people desperately sought a way to protect themselves and their loved ones from getting sick. One widely adopted method consisted of mixing two small cloves of garlic in a pint of fresh milk. People believed that drinking this cocktail in the morning, on an empty stomach, would prevent the feared disease.

Like those living through the great plague of London, many people searched for remedies that would keep COVID at bay, which is why claims that garlic could cure or protect people proliferated on social media. The claims prompted an exasperated World Health Organization to post tweets of caution.

Unfortunately, despite laboratory studies showing that garlic does indeed have compounds with anti-microbial properties, the idea of ingesting garlic to prevent becoming infected with any bacteria or virus is mostly folklore.

Folk remedies may sound benign, but they can hurt people. A 72-year-old woman ended up with a chemical burn on her tongue due to her daily use of raw garlic in an attempt to protect herself against the coronavirus, for example.

Medical folk wisdom

The idea of garlic as a blanket cure has its foundation in medical folk wisdom, which is an umbrella term for unproven, widespread beliefs about anything to do with health and disease.

Folk wisdom often has a certain level of seductive intuitiveness and generally originates from cultural beliefs as well as long-held traditions. Folk wisdom can involve herbal remedies, dietary recommendations and advice about following specific behaviours. It is often passed down by word of mouth through generations and may be one of the reasons myths about the causes and cures of diseases persist, despite the progress of medical science.

The unshakeable belief many people hold that eating before you go for a swim is dangerous, for example, has no scientific basis. Even though the logic seems compelling, the idea that eating before swimming causes drowning has been debunked by researchers.

Folk wisdom is complicated because on the one hand it broadly falls under the category of misinformation, but on the other it doesn’t quite fit with the usual class of misinformation (such as fake news or misleading advertising). If someone endorses folk wisdom, it is not necessarily a strong indicator they have anti-science beliefs.

People who believe in “starving a fever”, for example, can also be pro-vaccines. Likewise, it would not be unusual for a person who follows official health recommendations to also use folk wisdom as an additional safeguard against, for example, the coronavirus.

Don’t underestimate it

However, the idea that folk wisdom is predominantly benign might be why experts tend to pay less attention to it. For example, believing that drinking warm milk before bed helps you go to sleep is not going to harm you (even if it’s not true). However, other beliefs can be dangerous such as the idea that eating particular foods can bolster your immunity, which can lead people to think they don’t need to be vaccinated against the flu or COVID.

Folk wisdom, like other types of misinformation not backed by science, often proliferate on social media, which means it can pose a threat to public health.

For example, in 2020, when the UK went into lockdown, the Burns Centre at Birmingham Children’s Hospital saw a 30-fold increase in the number of scald injuries from steam inhalation. This was caused by a folk wisdom on social media that misled parents into believing that inhaling steam could prevent or treat respiratory tract symptoms. This was particularly disheartening because studies published worldwide since 1969 have highlighted the dangers of steam inhalation.

While some examples of folk wisdom have a level of biological plausibility, others do not. For instance, the belief that “an apple a day keeps the doctor away”, a medical folk proverb from around 1870, was probably based on the wisdom that apples are full of nutrients. Interestingly, scientists have found that though the vitamin content of apples may not be particularly exceptional, apples are considered a so-called functional food (which must meet a scientific criteria, unlike “superfoods”) because of the number of bioactive substances that they have which appear to be health promoting.

Folk wisdom isn’t likely to disappear anytime soon. So we need to understand what makes people believe in it and to what extent it challenges beliefs in science. There seems to be a complex relationship between beliefs in folk wisdom and what people actually do to protect their health. Understanding this relationship could be key to preventing its harmful effects. Lives may depend upon it.![]()

Katrine K. Donois, PhD Candidate in Psychology (Science Communication), Anglia Ruskin University, and Hassan Vally, Associate Professor, Epidemiology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The opinions expressed in VIEWPOINT articles are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of ARU.

If you wish to republish this article, please follow these guidelines: https://theconversation.com/uk/republishing-guidelines