New research calculates a dog’s life expectancy

VIEWPOINT: ARU expert looks at study examining how long different breeds will live

By Angus Nurse, Anglia Ruskin University

The UK has long been considered to have some of the strongest animal welfare laws in the world. Beginning with Martin’s act on the cruel treatment of cattle, through to the Animal Welfare Act 2006 and then Finn’s law to protect service animals, UK animal welfare laws have sought to reduce harm and cruelty to animals. But what happens when companion animals suffer or live shorter lives simply because of their genetic make-up?

On average, dogs live for 10-13 years, which is considered roughly equivalent to between 60-74 human years.

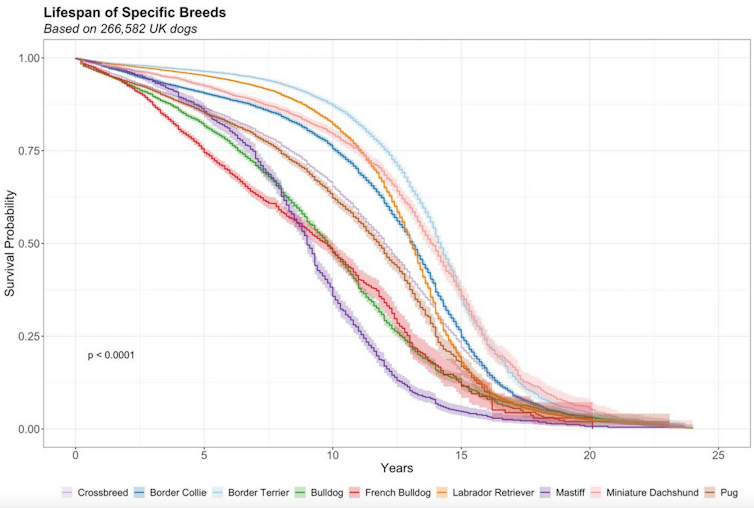

Small, long-nosed dogs have the highest life expectancies in the UK, while male dogs from medium-sized, flat-faced breeds such as English bulldogs have the lowest, according to a new study published in Scientific Reports. The research team’s results were based on data from more that 580,000 individual dogs from over 150 different breeds and could help identify those dogs most at risk of an early death.

The study is an important one, not least because of its size and scope, but also because very little research of this type had been done previously. We have life expectancy tables and research for humans that show how long we might be expected to live according to a range of factors. But there has been very little research into dog life expectancy that considered how different factors affect lifespan.

The research team created a database of 584,734 dogs using data from 18 different UK sources. These included breed registries, vets, pet insurance companies, animal welfare charities and academic institutions.

Dogs included were from one of 155 pure breeds or classified as a crossbreed, and 284,734 of the dogs had died before being added to the database. Breed, sex, date of birth, and date of death (if applicable) were included for all dogs.

Pure-bred dogs were assigned to size (small, medium or large) and head shape (short-nosed, medium-nosed and long-nosed) categories based on the Kennel Club’s literature. The researchers then calculated median life expectancy for all breeds individually and then for the crossbreed group. Finally, they calculated life expectancy for each combination of sex, size and head shape.

How long do dogs live?

This study from researchers at the Dogs Trust provides us with new information about the life expectancy of our canine companions. The researchers found that small, long-nosed female dogs tended to have the longest lifespans among pure breeds overall, with a median lifespan of 13.3 years. But breeds with flat-faces had a median lifespan of 11.2 years, and a 40% increased risk of shorter lives than dogs with medium-length snouts, such as spaniels.

Amongst the 12 most popular breeds, which accounted for more than 50% of all recorded pure breeds in the database, labradors had a median life expectancy of 13.1 years, jack russell terriers had a median life expectancy of 13.3 years, and cavalier king charles spaniels had a median life expectancy of 11.8 years.

Pure breeds had a higher median life expectancy than crossbreeds (12.7 years compared to 12.0 years), while female dogs had a slightly higher median life expectancy than males (12.7 years compared to 12.4 years).

The ethics of ageing

Research has previously suggested a growing popularity of small nose dogs such as bulldog breeds and pugs. These dogs have become fashionable and highly prized as pets, but are prone to various health problems, including brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (Boas).

This potentially life-threatening condition includes symptoms such as panting, overheating, exercise intolerance, retching, gastrointestinal signs and disturbed sleep patterns. So for some of these dogs, their life is potentially marked by suffering. This latest study shows they are also likely to live shorter lives.

This raises some questions about dog ownership and the ethics of breeding dogs likely to suffer from Boas. It might be seen as cruel to breed dogs that are either prone to or bound to suffer.

Other countries, including the Netherlands, have considered whether to limit the breeding of these dogs to prevent such suffering and we might expect UK law to consider this. But while the Animal Welfare Act creates an offence of causing unnecessary suffering, this relates to suffering of a protected animal that is already alive.

So, the act of breeding an animal with Boas is unlikely to be caught by these provisions and once in ownership of a dog with Boas, the owner has to treat that companion animal in accordance with its normal functions. Even though these conditions may be problematic if they are a natural part of the dog’s make-up, there is no offence of unnecessary suffering simply by having the dog.

The animal welfare acts include a duty to provide for good animal welfare. This means that dog owners should understand the needs of their chosen companion animal and should be confident that they can provide for them.

In addition to identifying possible directions for future research and animal welfare interventions, this study provides some important information that might help some potential owners decide which dog is right for them.![]()

Angus Nurse, Professor of Law and Environmental Justice, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The opinions expressed in VIEWPOINT articles are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of ARU.

If you wish to republish this article, please follow these guidelines: https://theconversation.com/uk/republishing-guidelines